Acupuncture for Multiple Sclerosis

Current Research

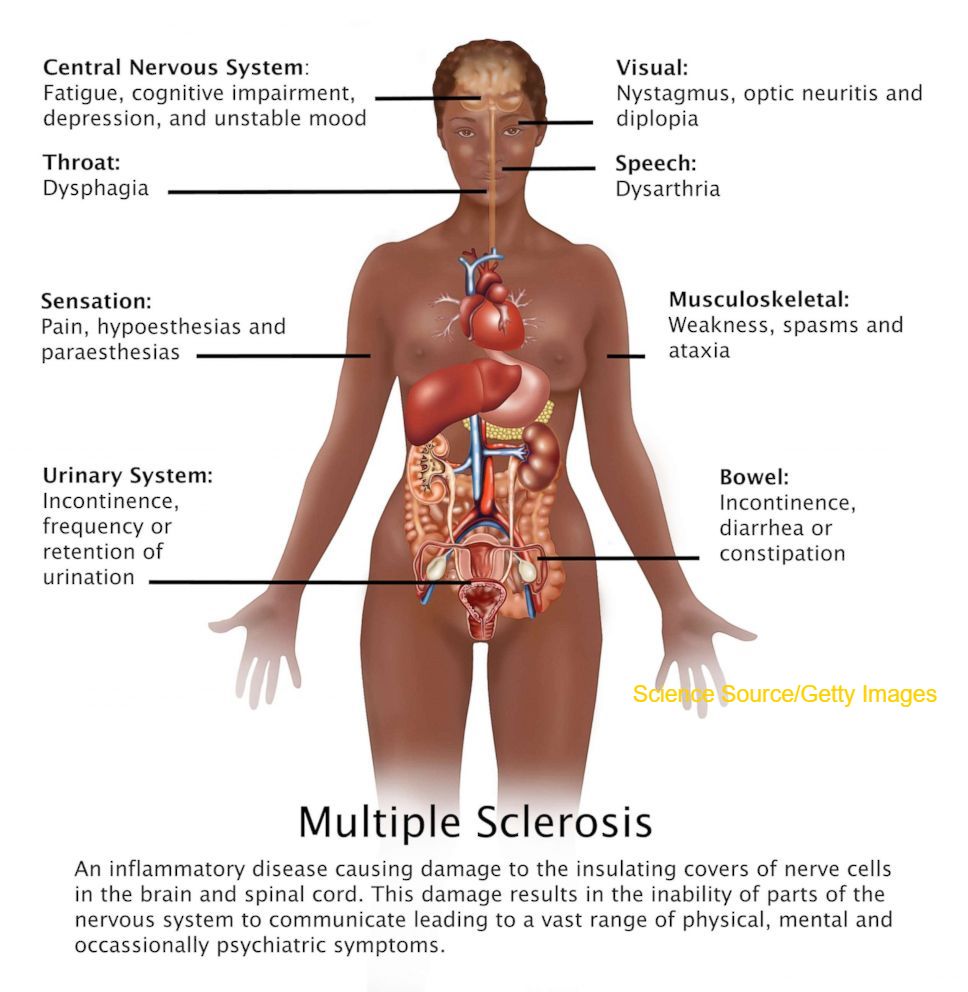

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease affecting 300,000 people in the United States and 2.3 million worldwide. (Rosati G, 2001) MS has a peak incidence between 25 and 35 years and is twice as common in women as men. (Hopwood, 2010, p138)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a severe autoimmune demyelinating disease that affects nervous system, has high morbidity and mortality and no effective targeted therapies are available. (Petrovics, 2017)

People with MS commonly use complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). Use of acupuncture to treat MS is common.

According to Acupuncture in Neurological Condition, Acupuncture has been recommended as a safe alternative intervention for pain relief in MS. (Van Den Noort, 1999)

Karpatkin et al. in 2014 published Acupuncture and Multiple Sclerosis: A Review of the Evidence, a literature search resulted in twelve peer-reviewed articles on the subject that examined the use of acupuncture to treat MS related quality of life (QoL), fatigue, spasticity, and pain. Many of the studies suggested that acupuncture was successful in improving MS related symptoms, for instance, acupuncture studies found a reduction of spasticity and improvement of fatigue and imbalance in patients with MS. (Criado, 2017) Electroacupuncture can significantly improve the quality of life of MS patients. The results suggest that the routine use of a self-report scale evaluating quality of life should be included in regular clinical evaluations in order to detect changes more rapidly. (Quispe-Cabanillas, 2012)

There have been three systematic reviews of acupuncture in general neurology (Lee 2007 and Rabinstein 2003 and Karpatkin 2014) three reports have concluded that the studies included showed no definitive data on the use of acupuncture for MS, although there might be a positive influence on the secondary symptoms. Some qualitative work, including that by Pucci et al. indicates that the use of acupuncture by MS patients is quite high and 61.5% of the patients interviewed in the Pucci study claimed that acupuncture was beneficial. (Pucci, 2004)

Chinese Medical Theory

2.1 Traditional Chinese Medical Approach. Multiple Sclerosis (MS) disease category depends on the primary clinical manifestations (Shi, 2003). In this case, MS falls into the disease category Atrophy Syndrome (Maciocia, 2008; Shi, 2003). The Pin Yin name for this disease is Wei Zheng, atrophy or Wei syndrome.

Atrophy or Wei syndrome is characterized by a weakness of the four limbs, absence of pain, often uneven in nature, leading eventually to paralysis. It is often seen as a description of MS. The theories informing a diagnosis of atrophy syndrome involve the invasion of Pathogenic Heat in the initial stages. This Heat dries up the body fluids and by doing so injures both the muscles and tendons. (Hopwood, 2010, p20)

According to Acupuncture in Neurological Condition, MS can be considered as four stages:

- 1st stage: Remission. There are no active symptoms, so the only therapy required will be preventive.

- 2nd stage: Meridian Problems. Pathogenic Heat or Damp invasion to meridians. Qi and Blood deficiency resulting Qi and Blood stagnation in meridians.

- 3rd stage: Middle Jiao involvement. Pathogenic Heat or Damp turn inward resulting Zang Fu pattern, Spleen Qi Xu, Liver Yin Xu

- 4th stage: Kidney Xu. Chronic Spleen Qi Xu and the Chronic Liver Blood Xu depletes both Kidney Jing and Kidney Yin.

According to Shi, based on TCM fundamental theories, deficiency of Liver, Spleen and Kidney and malnourishment of their extended tissues are the main pathogenesis of MS. Liver governs sinews and stores the Blood to nourish them, Spleen governs muscles, and Kidney governs bones and stores Jing that generates Marrow and nourishes the bones. Deficient Kidney and Liver cannot support their linked tissues, resulting in flaccidity and weakness of those tissues, and in Deficiency patterns, the lower extremities are most often affected (Shi, 2003). Chronic illness, secondary to interior factors and aging, results in dysfunction of these three organs, which leads to inadequate production of and distribution of Qi and Blood (Shi, 2003). Paresis and atrophy are signs of the critical phase of exhaustion of Jing and depletion of the Blood (Shi, 2003). In addition, Heat drying up the body fluids and injuring muscles and sinews will be seen in MS (Maciocia, 2008).

Treatment Plans

3.1 TCM approach:The general treatment principle will be to tonify Yin and Jin Ye or fluid balance. Most used acupuncture points are the Yang Ming meridians. Stomach points are used for the lower limb and Large Intestine points for the upper limb. (Hopwood, 2010, p20)

3.1.1 Acupuncture treatment. Body points can be selected according to local symptoms or according to the organ system that seems to be affected at the time. MS patients are subject to a considerable variation in severity of symptoms, and remissions and exacerbations are characteristic of the disease. A minimal selection of the appropriate points is necessary as overtreatment is very easy and patients can often be quite exhausted by their acupuncture treatment. (Hopwood, 2010, p141)

According to Acupuncture in Neurological Condition, below are points considered for different MS symptoms.

- For uncoordinated movement: GV 20 Regulation of central nervous system + Add Sishencong

- Fatigue or paresis in lower limbs: Right side- ST 31, ST 32, SP 10, ST 36, GB 34, GB 39, LR 3

- Irregular bowels CV 4, ST 25, LI 11, TE5, TE 6, UB28

- Support Kidney Yin: KD3, UB23

- Motor problems: Needle into muscle of interest, trigger point acupuncture to gain muscle relaxation and reduction in pain. Electroacupuncture to gain contraction of muscle.

- Consider scalp acupuncture over motor line.

When deciding how best to organize treatment sessions, it must be borne in mind that MS patients can easily be overtreated and will become very fatigued after just a few points. Do not leave the needles in too long and limit the points used. (Hopwood, 2010, p147)

TCM Clinical Trials:

A case of 66-year-old female patient who has been treated by both conventional and Chinese traditional medicine after diagnosis was confirmed in 2008 as MS and antiphospholipid syndrome associated with CNS vasculitis. She started acupuncture treatment in 2010 with herbal supplement therapy as well and patient had in total of 197 sessions with 10 session’s cycle and 2-3 months pause. Patient’s mobility was significantly improved after therapy, as well as vocal cord spasms and she gained back her articulation. Subjectively, patient also reported pain relief, mobility and fatigue improvement. Traditional Chinese medicine showed to be effective tool for pain and spasm relieving and can be powerful complementary tool in patients with chronic diseases, such as MS. (Petrovics, 2017)

In a recent study, acupuncture was provided in a group setting either immediately before or after each of eight classes designed to help women with MS build the skills necessary to improve their health and consequently their overall quality of life (Becker, 2017, p. 86). The participants self-reported fatigue, stress, pain, depression, anxiety, and sleep interference decreased significantly, and overall health-promoting behaviors, self-efficacy for health promotion, social functioning, and quality of life increased significantly (Becker, 2017, p. 86). In addition, focus groups held with the participants indicated that they responded positively to the combination of acupuncture with an efficacy-building health promotion intervention (Becker, 2017, p. 86).

A more recent study examined MS patients with fatigue and concluded that acupuncture (24 treatments within 12 weeks) added to usual care was significantly superior to usual care alone (Pach, 2017). Based on rating on the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) after 12 weeks (values 1‐7, with higher values indicating more fatigue). The primary outcome fatigue (mean adjusted FSS score after 12 weeks) was 4.7 (95% CI [4.4;5.1]) in the acupuncture group and 5.4 [5.0;5.7]) in the usual care group (difference: 0.6 [0.16; 1.07], p = 0.009) (Pach, 2017). Therefore, acupuncture may help MS patients with fatigue, particularly because of limited treatment options for these symptoms (Pach, 2017).

3.2 Adjunctive Therapies. Tapping with dermal needles in the affected areas and along the affected meridians may also be added to the treatment (Cheng, 2006, p.480)

3.3 Lifestyle Recommendations

Diet: The Spleen must be kept warm and dry, or it will cause Damp tends to settle in the muscles, causing numbness and weakening of muscles that progresses (Maciocia, 2008). Eating including warm and cooked foods, and avoiding alcohol, coffee, sugar; excessive dairy; fatty, fried or greasy foods; overly spicy foods; or cold and raw foods (Ni & McNease, 2000). Ni & McNease recommend eating small, frequent meals and drinking more fluids (2000).

Medicinal Food: Ni & McNease recommend some recipes for fatigue, particularly when it is chronic (2000).

- Daily juice of fresh water chestnut, lotus root, pear, watermelon and carrots

- Soup from lotus seed, white fungus and figs

- Stir fry with egg white, parsley, garlic and diced yams

- Soup from cabbage, azuki beans, winter melon and pumpkin

- Chicken soup with garlic, onions, scallions, ginger and daikon, eaten as soup or made into congee

- Congee of buckwheat and rice with chestnuts and longan fruit

Because nerves are ruled by the Liver in TCM, foods and herbs that build Liver yin help nerve inflammations like MS (Pitchford, 2002). In TCM, the most useful Liver yin tonics for treating MS include: leafy greens, mung beans and sprouts, millet, seaweeds, cereal grass concentrates (e.g. wheatgrass), micro-algae, and organic animal liver, which in biomedicine are some of the best sources of superoxide dismutase, a free-radical controlling, anti-inflammatory enzyme (Pitchford, 2002). In addition, lecithin-rich foods such as soybean products, cabbage, cauliflower and eggs (Pitchford, 2002).

Supplements: Vitamin D supplements (800 to 1000 units daily) may decrease the risk of disease progression and also reduce the risk of osteoporosis, especially in patients at increased risk (corticosteroids, decreased mobility). Serum vitamin D levels should be monitored to make sure that dosing is adequate. (Resources and Support, 2018)

Regular exercise: for example, treadmill, swimming, stretching, stationary biking, balance exercises, yoga, Tai Chi, with or without physical therapy, is recommended, even in advanced MS, because exercise conditions the heart and muscles, reduces spasticity, prevents contractures and falls, and has psychologic benefits.

Alternative Approaches

Pharmacology. Many MS patients do not require drug therapy. Most commonly used are forms of interferon, given intrathecally, intramuscularly or subcutaneously. Interferon has antiviral and immunomodulatory properties and is used because it is thought that MS may have a viral origin. (Hopwood 2010, p. 139)

Brief courses of corticosteroids to treat acute onset of symptoms or exacerbations that cause objective deficits that impair function (e.g., loss of vision, strength, or coordination); regimens include methylprednisolone 500 to 1000 mg IV once/day for 3 to 5 days, or less commonly, prednisone 1250 mg po per day (e.g., 625 mg po bid or 1250 mg po once/day) for 3 to 5 days (Levin, 2018). Recent data show that high-dose methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for 3 consecutive days) po or IV may have similar efficacy (Levin, 2018). Some evidence indicates that IV corticosteroids shorten acute exacerbations, slow progression, and improve MRI measures of disease (Levin, 2018).

If corticosteroids are ineffective to reduce the severity of an exacerbation, plasma exchange can be used for any relapsing form of MS but not for primary progressive MS (Levin, 2018). Plasma exchange and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be somewhat useful for severe, intractable disease (Levin, 2018).

Surgery is not commonly used in MS but in cases of very severe tremor deep brain stimulation can be tried with implantation of a device within the brain. In cases of disabling or painful spasticity a catheter or pump can be surgically placed in the lower spinal area to deliver a constant flow of medication. (Hopwood 2010, p. 139)

Screening for mood disorders

Screen should begin early after new diagnosis of a neurological condition

and be reviewed on regular basis. This is particularly relevant for those people with communication difficulties who commonly experience anxiety and depression but may be less able to express these concerns. (Hopwood 2010, p. 140)

Biomedical Consideration

The diagnosis of MS is not an easy one to make and relies more on elimination of other causes than a direct confirmation.

1. A positive diagnosis requires at least two separate episodes of neurological symptoms, weakness or clumsiness, tingling or numbness, vision problems or balance problems, as confirmed by a neurologist. Each episode must have lasted at least 24 hours and occurred at different times at least 1 month apart. (Hopwood 2010, p. 140)

2. In addition, a positive diagnosis requires symptoms that indicate injury to more than one part of the central nervous system, together with confirmatory magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and laboratory tests with findings consistent with a diagnosis of MS. MRI scans can be used to reveal lesions or plaques in the brain and a lumbar puncture may be done to evaluate the cerebrospinal fluid. MS sufferers tend to have a raised white blood cell count and abnormal levels of immunoglobulin. (Hopwood 2010, p. 140)

Community Resources

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) is an organization whose mission is to end MS worldwide (Resources and Support, 2018). They work to educate MS patients about their treatment options, resources and provide crisis intervention when necessary (Resources and Support, 2018). They also connect patients with each other in order to create a support system, as well as helping patients to find knowledgeable care providers in their area (Resources and Support, 2018).

References

Becker, H., Stuifbergen, A.K., Schnyer, R.N., Morrison, J.D., & Henneghan, A. (2017). Integrating acupuncture within a wellness intervention for women with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 35(1):86-96. doi: 10.1177/0898010116644833. Epub 2016 Jul8. PubMed PMID: 27161425

Cheng, Xinnong. (2006) Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

Claflin, S. B., Van der Mei, I. A., & Taylor, B. V. (2017). Complementary and alternative treatments of multiple sclerosis: a review of the evidence from 2001 to 2016. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 89(1), 34-41. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2016-314490

Criado MB, Santos MJ, Machado J, Gonçalves AM, Greten HJ. (2017) Effects of Acupuncture on Gait of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2017 Nov;23(11):852-857. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0355.

Donnellan CP, Shanley J. (2008) Comparison of the effect of two types of acupuncture on quality of life in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a preliminary single blind randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. Mar;22(3):195-205. doi: 10.1177/0269215507082738.

Hopwood Val, Donnellan Clare (2010) Acupuncture in Neurological Conditions. China. Elsevier Churchill Livingston.

Karpatkin, H. I., Napolione, D., & Siminovich-Blok, B. (2014). Acupuncture and multiple sclerosis: A review of the evidence. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014 1-9. doi:10.1155/2014/972935

Lee H, Park HJ, Park J. (2007) Acupuncture application for neurological disorders. Neurological Research ;29 Suppl 1:S49-54. PubMed PMID: 17359641.

Levin, M.C. (2018). Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/neurologic-disorders/demyelinating-disorders/multiple-sclerosis-ms

Maciocia, G. (2008). The Practice of Chinese Medicine: The Treatment of Diseases with Acupuncture and Chinese Herbs (2nd ed.). London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

Ni, M., & McNease, C. (2000). The Tao of Nutrition (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Seven Star Communications Group, Inc.

Pach, D., Bellmann‐Strobl, J., Chang, Y., Pasura, L., Liu, B., Jager, S.F., Loerch, R., Jin, L., Brinkhaus, B., Ortiz, M., Reinhold, T., Roll, S., Binting,S., Icke, K., Shi, X., Paul, F., & Witt, C.M. (2017). Acupuncture for patients with multiple sclerosis associated fatigue-a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17 | added to CENTRAL: 31 January 2018 | 2018 Issue 1; DOI: https://doi-org.pacificcollege.idm.oclc.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1782-4

Petrovics G, Ondrejkovicova A. (2017) Multiple sclerosis in an acupuncture practice. Neuroendocrinology Letters. 2017 May;38(2):87-90. PubMed PMID: 28650601.

Pitchford, P. (2002). Healing with Whole Foods: Asian Traditions and Modern Nutrition (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Pucci E, Cartechini E, Taus C, G. Giuliani. (2004) Why physicians need to look more closely at the use of complementary and alternative medicine by multiple sclerosis patients. European Journal of Neurology. 2004;11(4):263 7. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00758.x

Rabinstein AA, Shulman LM. (2003) Acupuncture in clinical neurology. Neurologist. May;9(3):137-48. Review. PubMed PMID: 12808410.

Resources and Support. (2018). Retrieved May 17, 2019, from https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Resources-Support

Rosati G. (2001) The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the world: an update. Neurological Sciences. vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 117–139, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100720170011

Shi, A. (2003). Essentials of Chinese Medicine: Internal Medicine. S. Lin & L. Caldwell (Eds.). Walnut, CA: Bridge Publishing Group.

Van den Noort S (1999) Multiple Sclerosis in Clinical Practice. New York: Demos Medical Publishing. Holland NJ.